Personal Questions

Did you have any background in art before meeting Hockney?

Yes, I did have a background. Although it would take too long to provide all of the relevant information, the following is an abbreviated account of some of the background I brought to this work as of the time I met David Hockney in March 2000. In addition to the information below, a recent 6-minute interview touches on one aspect of this.

[youtube id=”cFxM6suZuw8″ mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

Interview for 2009 University of Arizona’Leading Edge Researcher Award’

Art and Art History

I was first exposed to art and art history as a child, with the Des Moines Art Center being the first museum I ever visited, around the age of ten. Starting as a teenager, and continuing throughout my life, I have made visits to museums a high priority when traveling, resulting in me having visited at least 25 art museums in eight countries by age 30. By the time I met David Hockney I had visited major and minor art museums in 20 countries, many of them more than one time. As an undergraduate I purchased a copy of H.W. Janson’s History of Art (revised and enlarged edition, 1969) to study for myself outside of any formal class.

While attending the University of California, Irvine, I became friends with the now well-known artist Chris Burden, and attended a number of his performance art pieces. Chris is perhaps best known for his 1971 piece ‘Shoot’, where he had himself shot in the arm with a .22 caliber rifle.

[youtube id=”26R9KFdt5aY” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

A month earlier I had been one of three participants in his 6-hour piece 220. My connection with Chris Burden’s work certainly was influential in developing my understanding of the wide range of materials, artifacts and activities that can constitute visual art.

Starting in 1997 I worked closely with a number of art historians while serving as co-curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim’s The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition that opened in 1998, which set an all-time attendance record for that museum, and for which I shared an award from the U.S. Chapter of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art with the architect Frank Gehry, the then-director of the museum Thomas Krens, and my co-curator Ultan Guilfoyle. I was in contact again with Chris Burden at around that time, discussing mechanical design issues that had developed in his 1999 When Robots Rule: The Two-Minute Airplane Factory at the Tate Gallery in London, and I was an advisor for the 1999 Nam June Paik retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York.

Photography

I started taking photographs when I was less than eight, was given my first “real” camera (with adjustable aperture and shutter speeds) when I was twelve, and by sixteen had created a darkroom within the only bathroom of my family home, that I equipped with an enlarger I built from an old bellows camera. I made short 8 mm films while still in high school, experimenting with stop animation effects, and made a copier based on the Kodak Verifax® chemical process. I have continued designing and fabricating specialized photographic equipment for my imaging experiments throughout my life. Examples from the 1970s include a slide compositor based on a color enlarger head and precision x-y rotary stage, a high speed shutter triggered by an infrared beam and photocell, and a Fresnel lens for my 35 mm cameras.

My interest in still photography has included considerable experimentation with visual effects that I created with different types of imaging equipment and processes. My collection of cameras, lenses and photographic equipment constantly expanded from the time I was a child, so that by the time I met David Hockney in 2000 I owned a variety of cameras (up to 4″×5″) and lenses ranging from 8 mm circular fisheye to 800 mm super-telephoto, including tilt/shift bellows and six macro lenses for magnifications in overlapping ranges up to 20×. My initial purchases for my laboratory at the University of Arizona included two Zeiss® metallurgical microscopes with Nomarski differential interference contrast and brightfield/darkfield objectives for magnifications up to 1000×, both equipped with 35 mm and Polaroid® cameras, and I subsequently acquired both a Scanning Electron Microsocpe (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), providing magnifications up to approximately 100,000× and 1,000,000×, respectively. My photography has been represented by the New York agency Photo Researchers since the mid-1980s, and I estimate from my files that I had made at least 20,000 photographs and slides prior to meeting Hockney.

Since understanding and controlling light and shadow is critical for creative photography, the lighting equipment I owned prior to meeting David Hockney ranged from a fiber optic source for macrophotography, to a full set of 650 W studio lights with barn doors, scrims, etc. Meters included color temperature, 1-degree spot, and flash, with one meter having sufficient sensitivity to determine the correct exposure for a scene illuminated only by a single candle 80m/250ft. away.

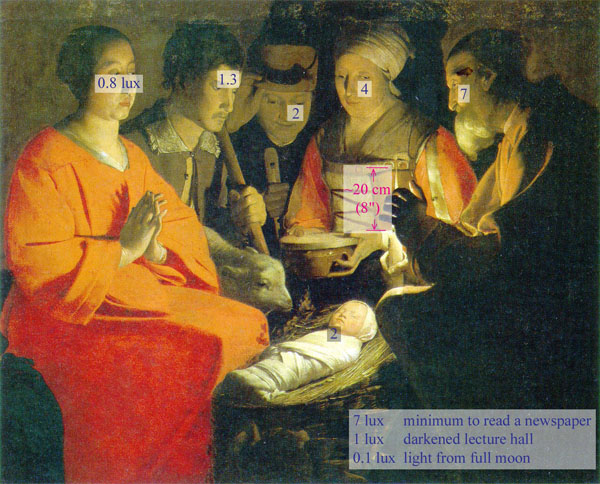

To make explicit the connections between some of the above examples, and the features within paintings in Hockney’s Secret Knowledge, images I created using my slide compositor demonstrate that, even when captured on film, “lens-based” images can be composites made up of a number of separate, unrelated elements (in van Eyck’s ‘Arnolfini Marriage’, although the chandelier is based on an optical projection, the dog almost certainly is not). All macrophotographs are limited by the constraints of the shallow depth-of-field that is intrinsic to every high magnification image (in Lorenzo Lotto’s ‘Husband and Wife’ for instance, the octagonal pattern is at the relatively high magnification of 0.56×). Understanding the complexities of lighting allows one to recognize creative representations of scenes made by artists (in de la Tour’s ‘Adoration of the Shepherds’ the woman at the left and the man at the right are represented as being equally illuminated by the candle whereas, even if the overall image were not a composite, if the candle actually were the sole light source of illumination the woman would be 9× darker than the man).

Overall, having created, processed, and manipulated a large number of images under a wide variety of conditions over the previous 40 years provided me with training for “previsualizing” what 3-dimensional scenes look like when projected by optics onto 2-d. When I met David Hockney this life-long, practice-based experience in art and imaging greatly aided in recognizing “optical looks” in portions of paintings. Subsequently, we were then able to investigate these images for the possible presence of optical artifacts from which we could extract scientific evidence.

Georges de la Tour, Adoration of the Shepherds (c1644)

Even in the highly unlikely event de la Tour had created this painting with all six subjects sitting in position the entire time he worked on it (i.e. if it were not a composite, and if it were created in its entirely in a single sitting), the woman at the left is ~3× farther from the unrealistically large candle flame than is the man at the right, so she “should” be ~9× darker (illumination falls off as 1/distance2). The fact that she isn’t darker means is that, although de la Tour has created a scene that conveys the impression of having been painted at night, illuminated only by the candle, the actual lighting he has represented in this scene is much more complex than that.

Optical Sciences

Since 1982 I have been a Professor of Optical Sciences at one of the best centers of optics research in the world, so obviously I have a scientific background in optics. One specific example that is directly relevant to this FAQ is that in the late 1980s, in collaboration with a group in Paris, my group produced a concave mirror (i.e. a “mirror lens”) that was used to make a magnified image of an intense plasma created by a high power laser. As listed elsewhere, roughly 25 of my scientific publications and one of my patents are in the area of optics for ultraviolet light and x-rays.

What was it like working with David Hockney?

“Indeed, much of the responsibility for the novel claims recorded in this book should surely rest with Falco… Just as Hockney was beginning to put together this wide-ranging book, and the experts were providing more scholarly and practical caveats, the optical scientist, Falco, made his dramatic entrance…. agog with Falco, Hockney hares off to find other askew tablecloths.”

Bernard Sharratt

The New York Times Book Review

December 23, 2001

“But Hockney shows all the signs of being a coddled celebrity whose every apercu is treated reverently by those flattered to earn his attention. He seems to have no one strong or trusted enough who could sift his intriguing insights from his banalities.”

Richard B. Woodward

The Weekly Standard

December 31, 2001

The above two assertions about our presumed working relationship couldn’t be more disparate. Sharratt portrays a naive artist “agog” with the calculations done by a scientist, while instead Woodward portrays a star-struck scientist in the thrall of a celebrity. The only thing these writers share is an implicit premise that belittling us personally somehow discredits the facts we have presented. However, neither assertion about our collaboration is anywhere close to the truth.

It is clear from Hockney’s earlier books that the various visual qualities, anomalies, disparities, etc. that eventually resulted in Secret Knowledge have been on his mind for years. That he would suspend his visual judgment developed over a long career simply because I showed him a calculation or two is absurd. Similarly, I have published over 250 refereed scientific manuscripts, maintain an active research program in optical physics, and have been elected Fellow of four scientific societies. It is equally absurd that I would risk compromising my scientific reputation by publishing something with Hockney unless I had great confidence in its correctness.

[youtube id=”7X5INWG9U7o&list=PL6DwVv2hudGastmAUvl-2wtukylLM24pq” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

A 40-sec. composite showing some of the equipment in my lab. This shows, in order: the largest of three Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) machines; repairing the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM); installing a new beam line and 4-circle diffractometer on the rotating anode x-ray source; and Brillouin light scattering equipment attached to another MBE machine. Click here to see a complete list of the equipment and facilities in my lab.

As a result of the different backgrounds we brought to this effort, developing the optical evidence that confirmed—and extended—Hockney’s visual discoveries was a collaboration between us in every sense of the word. Each of us brought to the task different sets of skills, both of which were required, and as a result we learned a great deal from each other. Lawrence Weschler, who wrote the original piece for The New Yorker that sparked our collaboration, wrote another article that documents what subsequently transpired after we met.

A final observation.

Perhaps it is of interest to mention an aspect of working in an area that has generated such wide media coverage. Whether or not they agree with us, all but a small percentage of the responses to this work—public or private—have been reasoned and thoughtful. Some of the exceptions to this have been interesting, ranging from someone who sent a package full of diagrams and excerpts from old books along with a four-page letter asking if I could use the material to prove whether or not space aliens had used optics to help design Mayan temples; to someone else who ended their letter, upset that we had “cast doubt” on van Eyck, with the hope that “Jesus, True God and True Man, may forgive you for your sins!” ; to a group that circulated a petition on the internet and picketed the Metropolitan Museum in New York denouncing us for having defamed the Old Masters. A related aspect of this last situation was described by Rex Dalton in a March 9, 2006 article in Nature.

Next: Technical and Historical Support for, and Objections to, Our Thesis >>