Art of the Motorcycle

- Science

- Motorcycles

- Art

- The Art of the Motorcycle

- The Art and Science of the Motorcycle

- Community Outreach

- College of Optical Sciences

Science

My interest in science can be traced at least as far back as the chemistry set I was given when I was nine or ten. One of my earliest experiments—supplemented by sulphuric acid that I somehow got my hands on— resulted in etching the porcelain from the bathroom sink. Undaunted, I embarked on my scientific career as an experimentalist.

Motorcycles

Ever since my first ride on the back of a motorcycle across Des Moines, Iowa at age ten, I’ve maintained an interest in these machines, and have never been without at least one motorcycle since I was 15½ (a Honda 50, that I crashed before I was 15¾).

1964: This is my first motorcycle, a Honda 50, that I got when I was 15½. The twisted handlebars and bent forks are the result of me hitting a car when I was 15¾.

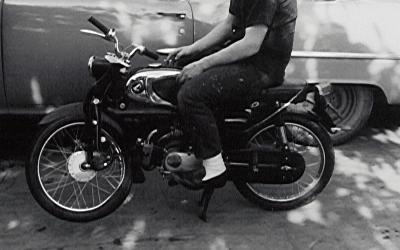

A Triumph 500 provided a diversion from studying for my comprehensive exams in graduate school, and many other motorcycles have played various roles in my life over the years.

[youtube id=”QnLnyIbxbwQ” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

1971: This photo and Super-8 film clip were taken during the summer I was studying for my comprehensive examination in graduate school. I still have this Triumph 500.

1981: Near the Wisconsin Dells on a Bultaco the summer before I moved from Argonne National Laboratory to the University of Arizona.

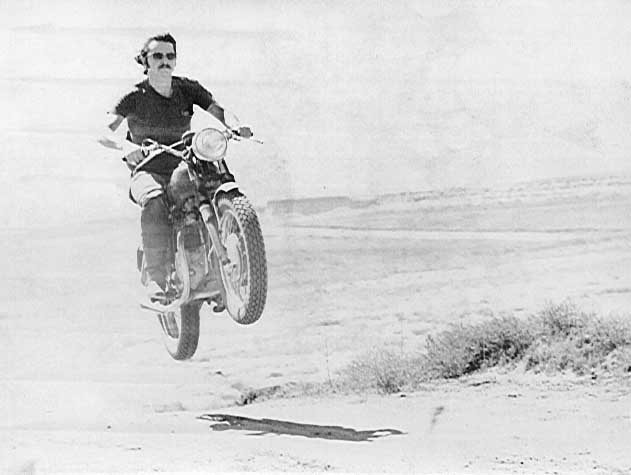

1993: On the island of Corfu, Greece on a Cagiva during one of the afternoon breaks in a NATO Advanced Study Institute where I was lecturing on x-ray optics.

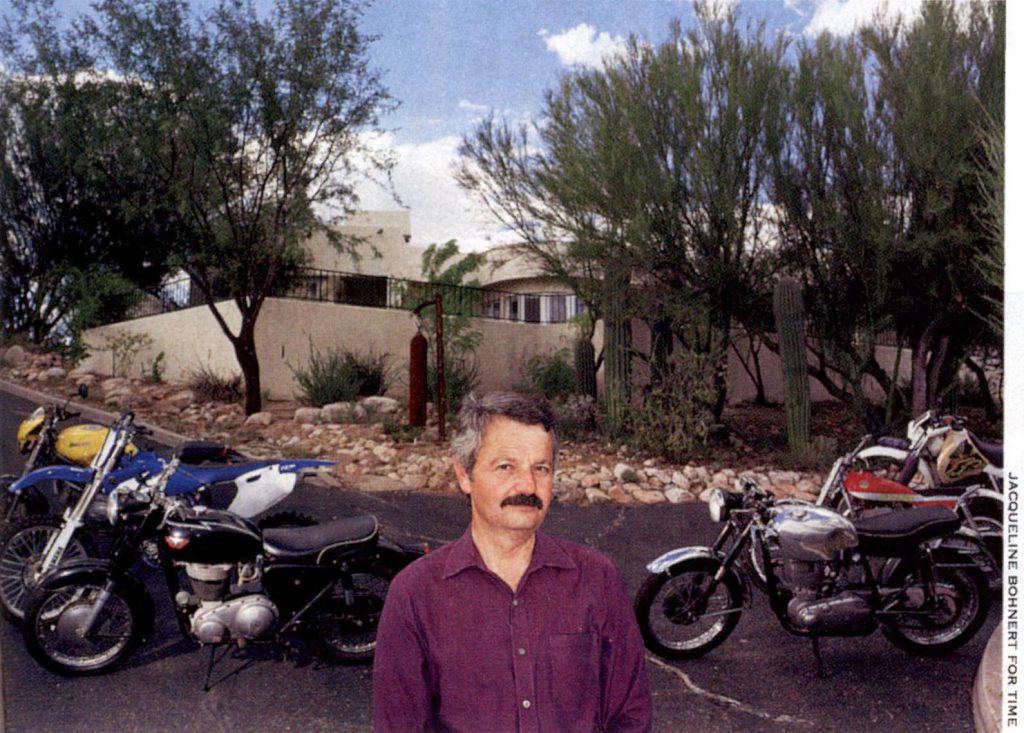

2002: An article in the October 21 issue of Time Magazine. This photograph was captioned “Falco owns 17 motorcycles and has ridden them as far afield as the Pyrenees and western Ireland.”

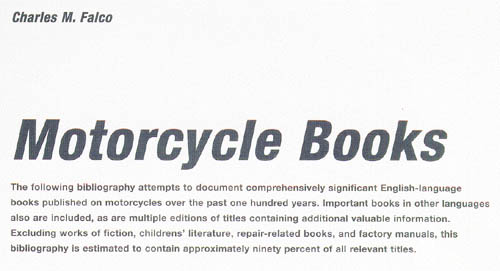

This passion for motorcycles also has scholarly manifestations. Over the past forty years I’ve assembled what is arguably the world’s largest private collection of English-language motorcycle books, with approximately 85% of all such volumes published since 1898. Starting in 1980, I’ve written about motorcycles, resulting in several dozen magazine articles and two books on the subject.

Scanned from the first page of the 30-page Bibliography (pg. 398–427) of The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition catalog, Thomas Krens and Matthew Drutt, eds. (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1998). I created this bibliography from the list of books in my own collection.

Art

Science and motorcycles make up two parts of a story, with the third being art. This also is a long-standing interest, pursued primarily through photography since receiving my first “real” camera at age 12. By age 30 I owned at least 15 lenses, ranging from 16 mm fisheye to 800 mm telephoto, including four bellows lenses for macro photography to magnifications of ~20×, and since 1985 my work has been represented by the New York agency PhotoResearchers. In 1971 I was one of three participants in Chris Burden’s six-hour conceptual performance art piece 220, and in 1999 I was an advisor to the Nam June Paik retrospective at the Guggenheim. More recently, in a collaboration with David Hockney, we discovered discover a variety of scientific evidence that supports and extends his theory that starting as early as c1425 some artists used optical projections as an aid to their painting. I’ve given over 300 conference talks and research seminars in some 24 countries, and whenever there has been free time on one of those trips, I’ve used the opportunity to visit art museums. As a result, I’ve probably spent more time in more museums than have many art history professors.

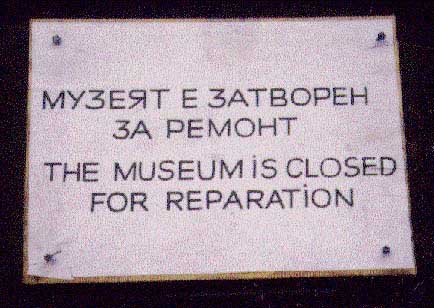

Unfortunately, this art museum in Varna, Bulgaria was one I wasn’t able to see when I spoke at a conference there in 1993.

The Art of the Motorcycle

The above three elements came together early in 1997, when the Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Thomas Krens, engaged me as Curatorial Advisor (subsequently changed to Co-Curator) for an exhibition on The Art of the Motorcycle being organized for the following year. Working with the Guggenheim’s Ultan Guilfoyle (Director, Film and Video Production Department), the two of us were charged with selecting all 111 motorcycles for that exhibition. The installation was to be designed by one of the world’s premier architects, Frank Gehry, in a building that is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most well-known works. This exhibition opened on June 26, 1998 for a three-month run, and to say it was well-received would be an understatement:

At the Guggenheim, you’re presented with a sequence of masterpiece bikes whose technological and esthetic developments remind you of, say, Brancusi’s paring down his sculpture until he arrived at the purest form possible.

- Peter Plagens. Newsweek Magazine, September 7, 1998.

The curators should be given credit for a highly imaginative celebration of the motorcycle as a 20th-century icon.

- Tony Walker. Financial Times (London), August 18, 1998.

It has become the most highly attended exhibition in the Guggenheim’s 61-year history…

- Carol Vogel. The New York Times, August 3, 1998.

The second place award for a design show goes to “The Art of the Motorcycle” and the installation designed by Frank Gehry. Thomas Krens, Ultan Guilfoyle, Charles Falco, and Matthew Drutt organized the show for the Guggenheim Museum.

- Best Design Exhibition of 1997–1998

- U.S. Chapter of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art

[youtube id=”WSPwLo-4sFY” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

Excerpts from a 1998 Guggenheim video directed by Ultan Guilfoyle

[youtube id=”tpSXVw2vAIA” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” maxwidth=”850″]

Excerpts from CBS 60 Minutes and introductions to 1999 talk at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and 2002 talk at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

After setting an all-time attendance record of 301,037 visitors at the Guggenheim in New York (June 26 – September 20, 1998), The Art of the Motorcycle traveled to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (November 7, 1998 – March 21, 1999), where the attendance of 320,000 was the highest since the King Tut exhibition of 20 years earlier. In fact, well before it closed in New York it already had become by far the most visited exhibition of industrial design ever presented. Subsequently, it was in Bilbao, Spain (November 24, 1999 – September 3, 2000) in an installation also designed by Frank Gehry, where attendance exceeded ¾ million. It next moved back to the U.S. (October 12, 2001 – January 5, 2003) to a building designed by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate for the Year 2000). The site was the then-new, now-closed Guggenheim Las Vegas, located at the Venetian Hotel along with the new Guggenheim-Hermitage (also now closed), where attendance was over 250,000. Total attendance at these four venues was over 2 million, placing it in the top five exhibitions ever presented by any museum. After completing its highly successful Guggenheim run, the name was licensed to Wonders Museum in Memphis (April 22 – October 30, 2005) and the Orlando Museum of Art (January 22 – July 23, 2006).

Within six months after the exhibition opened in New York 70,000 copies of the 432-page catalog already were in print, with Spanish and German editions published in mid-1999 (over 250,000 copies were in print by 2005). Since I wrote the opening essay, Issues in the Evolution of the Motorcycle, as well as the Bibliography, the success of the exhibition catalog made these by far my most widely read publications. Almost certainly more people have read that essay than the 250-some scientific publications of my physics career.

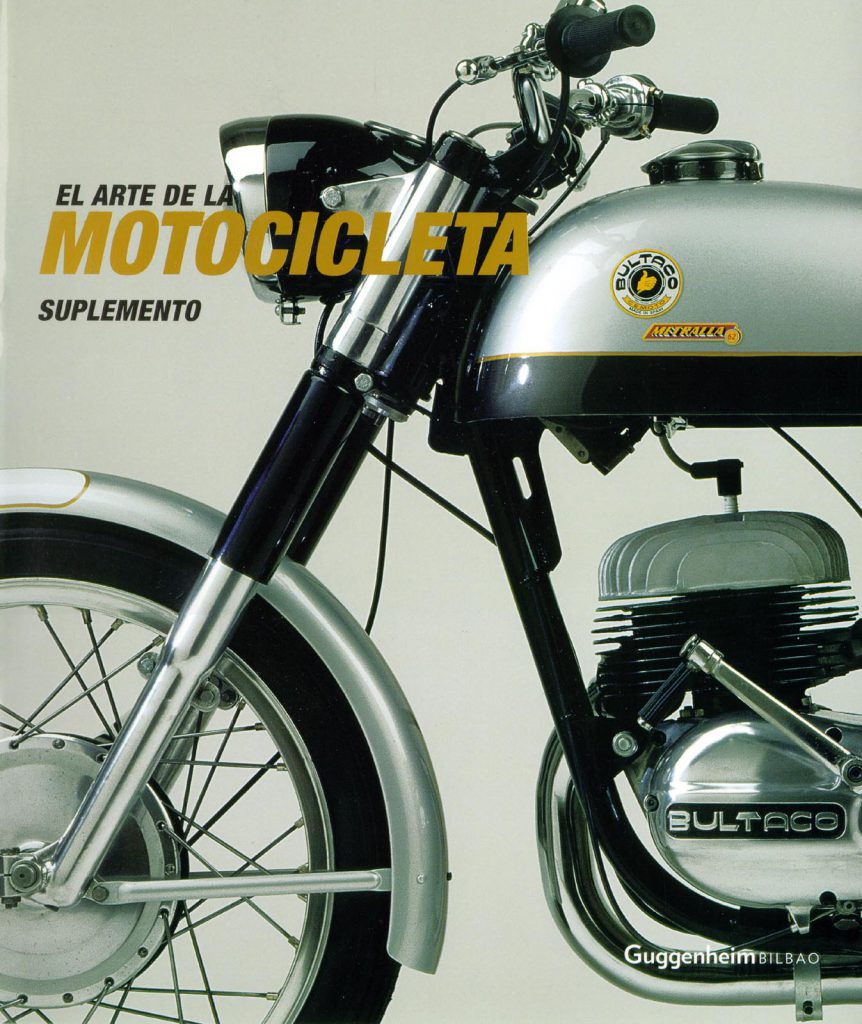

One of my motorcycles, a 1966 Bultaco Metralla, was in all four venues of the exhibition, and featured on the cover of the 1999 Spanish-language supplement. This motorcycle, a copy of the supplement, and several other of my items are in the “MotoStars: Celebrities + Motorcycles” exhibition at the Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum in Ohio, 2008–2009.

My Bultaco Metralla on the cover of the Spanish-language supplement that was published when the exhibition moved to Bilbao.

Ultan Guilfoyle and I, along with Thomas Krens and Matthew Drutt, shared an award with architect Frank Gehry from the U.S. Chapter of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art for Best Design Exhibition of 1997–1998. More recently Ultan collaborated with Academy Award-winning director Sidney Pollack as producer of the film Sketches of Frank Gehry. Sadly, Pollack passed away in 2008, and this turned out to be the last film he directed. In 2015 I was awarded the American Physical Society’s Dwight Nicholson Medal for Human Outreach with a citation that reads:

For his award winning “The Art of the Motorcycle” exhibition for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (co-curator), and his work with the renowned artist David Hockney on the optical science utilized by the grand master artists; each unique project has made the public aware of the contributions of science

to their daily lives.

The Art and Science of the Motorcycle

As illustrated by the record-breaking attendance at the Guggenheim, the history, technology, and aesthetics of motorcycles are of great interest to the public. Hence, as word of my involvement with this exhibition spread, increasing numbers of seminar requests began to sound something like “are you available to give us a physics seminar and, oh, by the way, also a talk in the evening on motorcycles?” In an era of sharply declining enrollments in science and engineering, audiences that have been more than 500 for these public lectures have provided an ideal forum for communicating other issues to the general public. Issues such as the importance of scientific research to their quality of life (e.g., creating unique new materials), that having a career as a successful scientist doesn’t necessarily require abandoning other satisfying aspects of life, and that there are scientists without the stereotypical personalities depicted in movies.

Click Here for abstract and list of talks given on The Art and Science of the Motorcycle

Community Outreach

Over the past fifty years the public has developed an image of our profession that isn’t entirely positive. Clearly, to the extent scientists are thought of as having only a narrow perspective, or are believed to be engaged in research far removed from society’s needs, it doesn’t serve us well with legislators, nor with young people deciding on a field of study. For scientists and engineers who think it is important to devote a few hours a year to altering our public image, various professional societies have programs to foster appropriate community outreach activities. Relevant sites include ones maintained by the American Physical Society (APS), American Society for Engineering Education, European Physical Society (EPS), National Academy of Sciences (NAS), Optical Society of America (OSA), and the SPIE .

College of Optical Sciences

Finally, if you are a student interested in science or engineering, and are looking for a place to do your undergraduate or graduate work, I strongly encourage you to investigate the programs offered by the College of Optical Sciences. Here at the University of Arizona you will find one of the world’s premier optics centers, an interesting and highly active faculty, and a dedicated support staff to help prepare you for an exciting and rewarding career in a wide range of optics-related areas.

Return to Scientific Staff, Home, or Art~Optics